Beyond Hours: The 'Whole Pilot' and the Safety Gap

I didn’t grow up around aviation. I wasn’t one of those kids who lived at the airport or knew what a VOR was before middle school. The first time I flew an airplane was in the military. Everything I learned about flying—how to think about it, how to talk about it, how to take it seriously—came from that environment.

My first squadron commander was a man who I learned a lot from, both as a pilot, and as a military officer. He used to say that just because you were a special operations pilot didn't make you special.

Strive to be, what he called, a "quite professional."

I ended up flying for fourteen years, in sixty-seven countries, across roles that forced me to think about aviation not just as a skill, but as a profession. I was a safety officer. A training officer. An ADO. A deployed squadron commander. In each of those roles, flying was never just about manipulating an aircraft ("trees get bigger or trees get smaller" as I like to say). It was about discipline. About predictability. About doing things the same way every time, especially when things weren’t going well.

Standard operating procedures weren’t a suggestion. They were the foundation. Regardless of who I flew with, I knew what callouts I was going to hear. I knew the profiles we were going to fly. If someone wanted to do something differently, that difference was briefed ahead of time. And if it wasn’t briefed, it was debriefed—not as a personal criticism, but as a professional expectation.

That was the only aviation culture I knew.

When I eventually transitioned into Part 91 flying, I walked into a world that felt completely divorced from that structure. Thousands of flight departments. Tens of thousands of pilots. All operating differently. Different standards. Different procedures. Different definitions of what “professional” even meant.

That, by itself, isn’t inherently bad. Aviation is broad. It’s diverse. Freedom has always been part of its appeal. Like any industry, there are good actors and bad actors. I wasn’t shocked by the variation. What surprised me was how normalized that variation was—especially in operations involving expensive aircraft and high-stakes missions.

When I accepted a job as a Chief Pilot for a single-pilot certified aircraft, I couldn’t shake the habits I’d built. I would pre-brief myself before a flight, as strange as that might sound to someone watching from the outside. I would talk out loud in the cockpit. "Flaps" "Gear" "Flaps" - Callouts that no one else could hear.

Not because anyone required it. Because not doing it would have felt wrong.

For a long time, I didn’t concern myself much with how other people operated. It didn’t affect me. I knew what I personally owed the airplane, the mission, and the people trusting me with both. That felt sufficient.

That changed as I started building Flying Company.

As I began talking daily with owner-operators, flight departments, management companies, and professional pilots across the country, the differences in operating culture became impossible to ignore. Not just in technique, but in mindset. In how people thought about responsibility. About preparation. About accountability. About what it actually means to be a professional pilot.

Over time, something that had always felt abstract became very clear: once you see the range of how Part 91 is actually flown, the safety gap between Part 91 and Part 121 stops being mysterious.

It doesn’t require a dramatic explanation. It emerges naturally from the way the system is structured—or, more accurately, from the way it often isn’t.

For years, our industry has relied on 'hours' as the primary shorthand for safety. Total time. Total PIC. Total Multiengine or Turbojet. Those numbers matter. They always will. But they’re often treated as if they’re sufficient on their own, as if accumulating hours somehow guarantees good judgment, discipline, or consistency.

If that were true, Part 91 business aviation would already look a lot more like Part 121. It doesn’t.

The pilots flying airliners are not categorically better pilots. In many cases, they’re the same people flying under different rules, on different days, in different aircraft. What changes isn’t who they are. It’s the environment they operate in.

Airlines don’t rely on individual professionalism as a hope or a personality trait. They institutionalize it. Procedures are standardized, trained, evaluated, and enforced. Deviations are examined not only when something goes wrong, but because deviation itself is treated as meaningful. Accountability exists upstream of the accident chain.

Part 91 doesn’t work that way, and it's unreasonable to expect it to.

In Part 91, professionalism is largely self-defined. Some operators have detailed SOPs; others don’t. Some pilots pursue training well beyond the minimums; others stop exactly at what’s required. Safety management systems exist, but usually because someone made a deliberate choice to adopt one—not because they’re expected as a baseline.

None of this makes Part 91 reckless. But it does make it uneven. And unevenness is where risk accumulates quietly.

This becomes especially consequential when pilots are hired to fly aircraft they do not own.

There is a meaningful distinction between exercising personal risk and assuming professional responsibility. When you’re hired to operate someone else’s aircraft, you are no longer just exercising discretion on your own behalf. You are entrusted with an asset, with passengers, and with the downstream consequences of your decisions—legal, financial, and human.

At that point, legality is the floor, not the objective.

Professionalism, in that context, is not an abstract ideal. It’s observable behavior over time. It shows up in how seriously a pilot treats procedures when no one is enforcing them. In whether training is something to get through or something to build on. In whether operating legally is seen as sufficient or merely necessary. In whether accountability is welcomed as part of the job or resisted as an intrusion.

This is where the conversation around safety in Part 91 needs to mature.

The question is not whether a pilot is qualified. The FAA already answers that. The harder—and far more important—question is how that pilot operates when the system around them doesn’t force the issue. When structure is thin. When discretion is high. When the only thing enforcing professionalism is the pilot themselves.

For the people responsible for hiring pilots—owners, operators, chief pilots, hiring managers, safety managers—that question is extraordinarily difficult to answer. The information is fragmented. The signals are noisy. Judgment, discipline, and safety culture don’t fit neatly into a logbook. As a result, many hiring decisions default to what’s easiest to defend: hours.

That response is understandable. It’s also incomplete.

If professionalism is going to matter in Part 91—and it has to—then it needs to become legible. Not perfectly measurable, not reducible to a score, but visible enough to be discussed honestly and evaluated responsibly.

That requires a shift in how we think about pilots.

For most of the industry, pilot evaluation still revolves around a narrow set of variables. Those variables describe exposure, not conduct. They tell us how much someone has flown, not how they operate.

What’s missing is a way to think holistically about professionalism—one that accounts for both objective qualifications and the qualitative behaviors that actually determine outcomes.

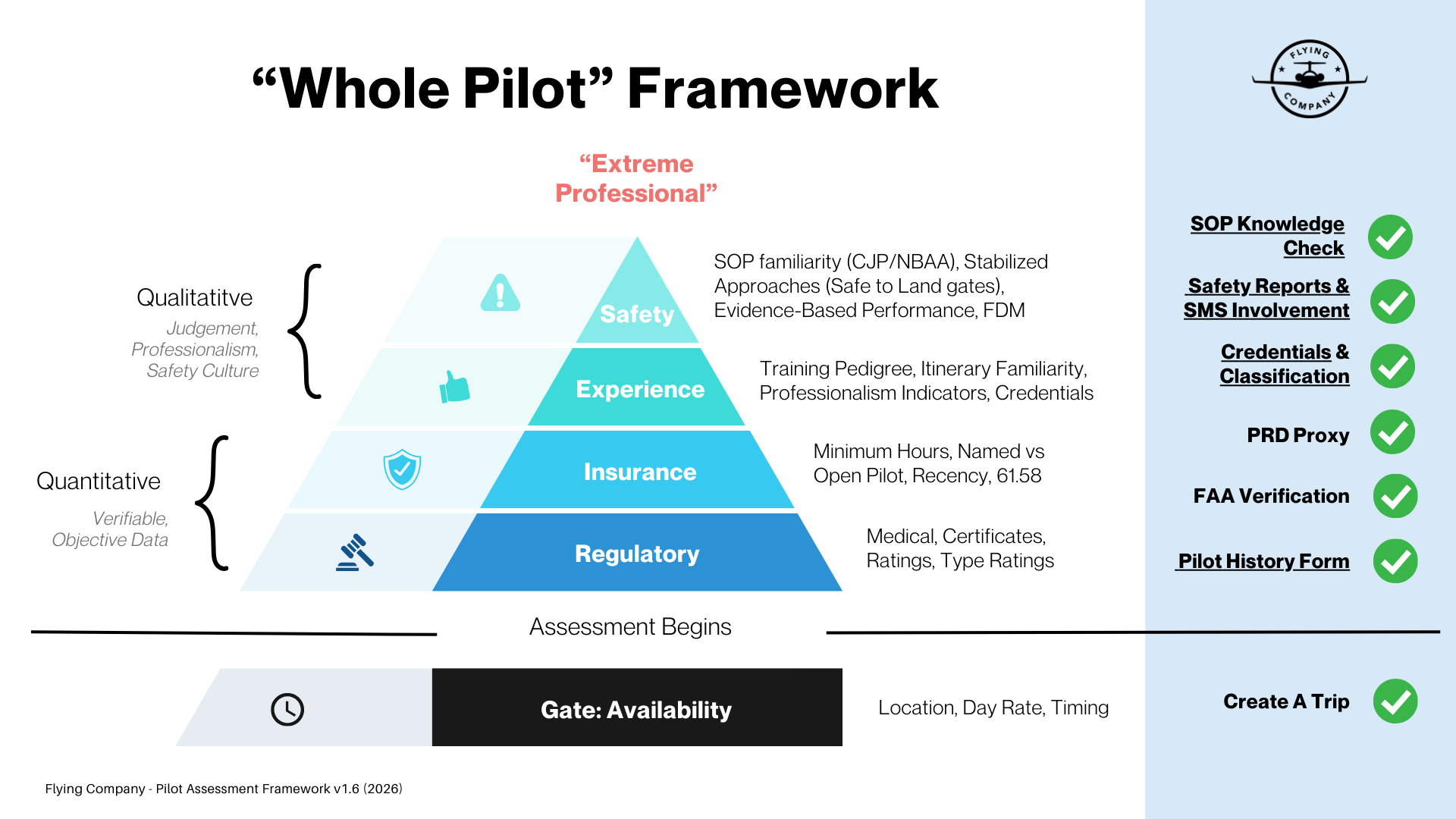

Over time, I’ve come to think of this as a “whole pilot” framework. Not as a proprietary system, and not as something that belongs to any one company. But as a reference point. A way of organizing what many people already care about, but struggle to articulate.

A whole-pilot lens doesn’t discard hours. It contextualizes it. It considers regulatory discipline, training pedigree, and currency, but it also considers preparation, judgment, and consistency. It asks how a pilot approaches standard operating procedures, how they think about risk, and whether professionalism shows up as a pattern rather than a claim.

Some of these elements are easy to verify. Others are qualitative, but no less real. What matters is not that every dimension be perfect. What matters is that professionalism leaves a trace—that pilots who take the craft seriously are willing to make visible how they operate, not just what they’ve accumulated.

For operators and hiring managers, this reframing matters. Hiring a pilot is not just a staffing decision. It is the delegation of judgment. And delegating judgment without understanding how that judgment is exercised is an unacceptable gamble, no matter how impressive the logbook looks.

A whole-pilot perspective doesn’t eliminate risk. Nothing does. But it aligns hiring decisions more closely with the behaviors that have consistently proven to reduce it.

This is not a call for more regulation. Aviation already has plenty of it. Nor is it a call to turn Part 91 into Part 121. The freedom and flexibility of Part 91 are worth preserving.

If Part 91 business aviation wants to close its safety gap—not in theory, but in practice—it won’t do so by chasing higher minimums. It will do so by elevating professionalism from an assumption to an expectation, and by giving both pilots and operators better ways to recognize it, demand it, and sustain it.

Safety is not something that begins with the accident flight. It is built quietly, long before, in how seriously we take the profession when no one is forcing us to.